Mary White Rowlandson

The Author of an American Mythology

C. 1637-1711

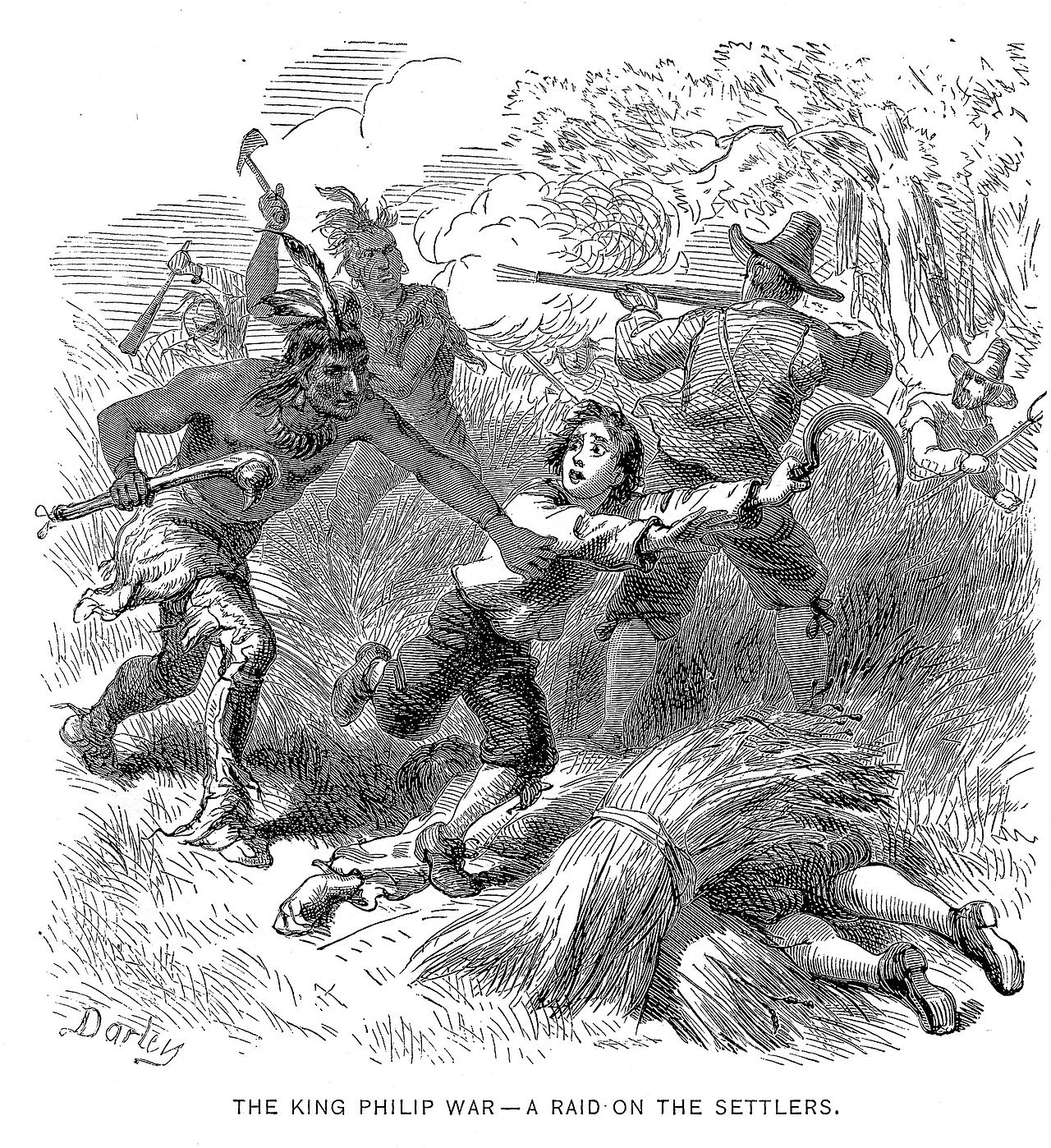

In 1676, the New World was still a dark and mysterious place for the English colonizers that had begun settling there in 1607(1). Adding to the uncertainty, there was a war raging between the indigenous inhabitants of New England and the colonists and their allies. What began as ever-increasing demands and tensions between on the Wampanoag chief, Metacom, and the colonizers, quickly devolved into something much more violent. In June of 1675, the Wampanoags raided a colonial settlement, killing 11, in retaliation for the murder of one of their own the day before. This triggered further raids on colonial settlements and the wholesale slaughter of Indians and the burning of their villages.

King Philip’s War would come to be recognized as the bloodiest and most vicious conflict in Colonial American history. With the number of lives lost and forever altered, few individuals - especially women - resisted being swallowed by the overwhelming statistics around the conflict. Those that do stand out and add their voices to the historical record give it crucial color and depth, and often did so against great odds, becoming towering figures in the creation of an American mythology that can still be felt today.

Mary White was not the type of woman that seemed destined for great adventure. Born around 1635, she was one of nine children born to John and Jane White in Somersetshire, England. The family left England sometime before 1650 to settle in Salem, Massachusetts, and then migrated to Lancaster on the frontier. It was there that Mary met Joseph Rowlandson, a minister. Together they built a home on a hill above Ropers Brook, and Mary gave birth to four children, three of which survived.

Daily life in the colonies would have been challenging, tedious, dangerous, and rife with religious superstition. While there would not have been much time for leisure activities, the Puritans put great value in literacy because it was their belief that everyone should be able to read the Bible. However, the ability to read and write did not necessarily liberate a Puritan’s mind from false beliefs. The indigenous inhabitants in particular were a prime target for the superstitions that continued to grow and develop with each passing year.

Even those that encouraged friendly relations with the Native populations warned that they were aligned with “dark forces.” They were thought to “cast spells, wither crops, hurt or heal at will, by drawing on the power of evil spirits of the devil himself.” (2) But it didn’t take much to cause suspicion in the colonies. If a woman could walk down a dusty road and arrive at her destination still looking neat, she was suspected of being a witch. The bar was quite low.

For the Puritans, the threat of and Indian raid, especially during King Philip’s War, was an ever-present worry. Still, it must have been a surreal experience to realize that it was actually happening to you. For the most unfortunate of settlers, their worst nightmares came true without warning.

For the Puritans, the threat of and Indian raid, especially during King Philip’s War, was an ever-present worry. Still, it must have been a surreal experience to realize that it was actually happening to you. For the most unfortunate of settlers, their worst nightmares came true without warning.

“On the tenth of February, 1676, came the Indians with great numbers upon Lancaster. Their first coming was about sun-rising; hearing the noise of some guns, we looked out; several houses were burning and the smoke ascending to Heaven. There were five persons taken in one house … There were two others who, being out of their garrison upon some occasion, were set upon; one was knocked on the head, the other escaped. Another … was … shot and wounded and fell down … Another, seeing many of the Indians about his barn, ventured and went out, but was quickly shot down. There were three others belonging to the same garrison who were killed …

At length the came and beset our own house, and quickly it was the dolefullest day that ever mine eyes saw … About two hours … they had been about the house before they prevailed to fire it (which they did with flax and hemp which they brought out of the barn …).

No sooner were we out of the house but my brother-in-law (being before wounded, in defending the house, in or near the throat) fell down dead … The bullets flying thick, one went through my side, and the same (as would seem) through the bowels and hand of my dear child in my arms …

Of thirty-seven persons who were in this one house, none escaped either present death or a bitter captivity, save only one … There were twelve killed; some shot, some stabbed with their spears, some knocked down with their hatchets …

I had often before this said that if the Indians should come I should choose rather to be killed by them than taken alive; but when it come to the trial my mind changed. Their glittering weapons so daunted my spirit that I chose rather to go along with those … than that moment to end my days …”

Mary’s daughter did not survive her injuries. The Native captors buried her on a hill and allowed Mary to go to the grave to mourn, and then they allowed her to see her other daughter, Mary, who was being held in another part of the village.

“I went to see my daughter Mary, who was at this same Indian town at a wigwam not very far off, though we had little liberty or opportunity to see one another. She was about ten years old, and taken from the door at first by a praying Indian and afterward sold for a gun.”

During her captivity, the party moved often, probably due to the English army which was following them. Mary ate ground nuts, bear meat, and corn meal, but was always hungry. She also did work by making and mending shirts for the Indian men for which she was paid. She was then assigned to work for a woman named Weetamoo. Mary described Weetamoo as a rather fashionable figure,

“… dressing herself neat [ly] as much time as any of the gentry of the land; powdering her hair and painting her face, going with necklaces and jewels in her ears and bracelets upon her hands. When she had dressed herself, her work was to make girdles of wampum and beads.”

Finally, after eleven weeks in captivity, Mary was ransomed for £20 and released.

In her account, Mary often recounts passages of Biblical scripture that gave her hope and confidence during her ordeal. She was, like most Puritans, deeply religious. Her captors understood this and, after a raid on the town of Medfield, Massachusetts, offered her a Bible that had been taken as plunder. This small act brought her much comfort during the remainder of her captivity.

When Mary was told that she would soon be released, she dared not hope that it was true. Yet, she put her faith in God to lead her to safety. The promise of release was not a lie, though. Since all of their property had been destroyed in the raid, Rev. Joseph Rowlandson - who had been away during the raid (8) - raised the amount for her release from friends in Boston. Mary was quickly released, but without her children. A week later, the Governor and Council met with the Indians and secured the release of her sister and children. Her son, Joseph was ransomed for £7, and her daughter, Mary, was released without a ransom.

By her own account, Mary’s ordeal deepened her faith in God. However, it’s unclear whether this effect was felt by those that consumed her story. Following her release, she became an instant celebrity. Perhaps because of this stardom, Mary and her family “removed” from Boston to Wethersfield, Connecticut.(4) When Rev. Rowlandson died, church officials gave Mary a pension of £30 a year. She then moved her children to Boston where she wrote the narrative of her capture. For some time it was believed that Mary died before the publication of her autobiography, but then scholars found that she had simply remarried, becoming Mary Talcott. Her manuscript was published in 1682, but she did not die until 1711 around the age of 73.(5)

The “captivity narrative” became one of the preeminent genres in America. While such stories have fascinated people for centuries, it was the particular narratives that came out of the “wilds” of the New World that had an especially profound effect on the shaping of the fledgling country. While captivity narratives did recount the facts about a person’s captivity by enemies (especially those considered “uncivilized” by readers), they often had a much darker intent as well. Often the facts of captivity itself came second to commentary about the religious and political beliefs of the writer. Encased in an action-packed shell of overcoming a perilous situation, captivity narratives were often not much more than propaganda, spreading religious ideology, xenophobia, stereotypes, and ideals about conquest and expansion.(6)

The fact that Mary Rowlandson’s account had a massive impact on the public at the time and became a classic example of the American captivity narrative isn’t in dispute. What is less certain is whether or not Mary’s words were really her own.

Increase Mather was an influential Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony around the same time that Mary was writing and publishing her book. Scholars such as Gary Ebersole and Kathryn Derounian-Stodola have argued that it was really his influence that made Mary’s account what it was. They cite similarities to another Puritan book, Jeramiad, and identify Mather as the anonymous author of “The Preface to the Reader” in Mary’s book.(5)

Yet, while Mary’s account of her captivity does contain a vast number of religious citations, and while it laments her treatment, she also acknowledges some of the humanity and kindnesses of those that captured her. After watching her home burn to the ground and the killing of many people, including her child, it would be understandable for her to hate her captors. Instead, she added important anecdotes describing the humane ways in which they treated her.

“There one of them asked me why I wept. I could hardly tell what to say: Yet I answered, they would kill me. "No," said he, "none will hurt you." Then came one of them and gave me two spoonfuls of meal to comfort me, and another gave me half a pint of peas; which was more worth than many bushels at another time.”

“One bitter cold day I could find no room to sit down before the fire. I went out, and could not tell what to do, but I went in to another wigwam, where they were also sitting round the fire, but the squaw laid a skin for me, and bid me sit down, and gave me some ground nuts, and bade me come again; and told me they would buy me, if they were able, and yet these were strangers to me that I never saw before.”

“I went to one wigwam, and they told me they had no room. Then I went to another, and they said the same; at last an old Indian bade me to come to him, and his squaw gave me some ground nuts; she gave me also something to lay under my head, and a good fire we had; and through the good providence of God, I had a comfortable lodging that night. In the morning, another Indian bade me come at night, and he would give me six ground nuts, which I did.”

While it was not uncommon for captivity narratives to embellish or sometimes include outright lies in their accounts, Mary’s always remained surprisingly even-handed. In it she explains that, “not one of them ever offered the least abuse or unchastity to me in words or action.” This alone makes her work stand out from the rest.

For women in Colonial America, stoping was never an option. No matter what traumas a woman faced, no matter how many obstacles she encountered, she was expected to remain a pious Puritan, a diligent wife and mother, and a contributing member of society. Even though Mary faced hardships that made her famous in her time, she was not exempt from the expectations placed upon Puritan women. Yet, her account shows a strength of character and objectivity that sets her apart. Although her narrative and others in the genre were used as justification for the mistreatment of Native Americans and expansion West, it also provides and invaluable glimpse into the psyche of Puritan women, Colonial American culture, gender roles, and race relations at the time.

-

(1) https://www.historyisfun.org/jamestown-settlement/

(2) https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1722/daily-life-in-colonial-america/

(3) https://archive.org/details/colonialwomen23e00caro/page/172/mode/2up?q=rowlandson (181)

(4) https://rowlandson.nrsd.net/families/about_us/history_of_m_r_e

(5) Derounian-Stodola, Kathryn Zabelle; Levernier, James Arthur (1993), The Indian Captivity Narrative, 1550-1900, New York: Twayne Publishers, ISBN 0-8057-7533-1

(6) https://sites.google.com/a/umich.edu/from-tablet-to-tablet/final-projects/captivity-narratives-in-colonial-america-fons-14

(7) https://www.learner.org/series/american-passages-a-literary-survey/utopian-promise/mary-rowlandson-c-1636-1711/#:~:text=Rowlandson%20tells%20her%20readers%20that,members%20of%20the%20Puritan%20community.

(8) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/851/851-h/851-h.htm